Last October I toured New England, Holland, Germany and Sweden with my old pal Jim Kweskin. I had a few solo gigs in there too. Later in November, Jim and I did a few dates in the Southwest before heading to Austin and Berkeley in December to play with the Texas Sheiks. Here’s a rundown…

In New England, my time was spent gigging, visiting friends and family on Martha’s Vineyard and doing promotion for the new Texas Sheiks album. The tour started with a gig in Marblehead, Mass, with Jim and “Spider” John Koerner. I can’t imagine two guys with whom I’d rather share the night. Back in the 60s, Koerner was always my favorite — the most unique of all of us young white guys playing acoustic blues. John wasn’t a copier. He had his own herky-jerky funky rhythm thing going on. John spent a lot of time in my neighborhood of Cambridge, Mass. and he was comfortable there. It’s because Cambridge wasn’t New York (he has said as much in interviews). Cambridge was much like Minneapolis, with music as a social thing. We played and listened to music every day and night and, with few exceptions, no one on the scene was planning anything particular in the way of a career. New York on the other hand was all about “making it.” At least that’s how we saw things generally.

The Marblehead gig was the first test of the new Kweskin / Muldaur duo. Jim and I had spent the summer working up arrangements for new material and I’d never had a better time rehearsing. We worked hard and it paid off.

People think that the Jim Kweskin Jug Band of the 60s was a devil-may-care walk in the park. It was not. It was a well-rehearsed walk in the park. Every detail was worked out so that by the time we hit the stage we could let it rip… so this is what Jim and I did during the summer of ‘09. During rehearsals, I often thought of our jug and tub player, Fritz Richmond, and how hard he used to work on arrangements, and how much he would have loved to be with us. I will always miss his spirit and dedication.

Marblehead was followed by another duo date in Providence and a couple of solo dates for me. Then I headed to NYC to do a little promo for the Texas Sheiks album. I wasn’t particularly looking forward to doing this, but I should have been. Our promotion firm set up some very nice interviews, including one with Serius Radio.

It was this interview that surprised me the most. As I was going through the various security points on my way into the studios of their midtown Manhattan offices, I was saying to myself, “Gee, has it come to this? Mainstream American radio? In a midtown corporate office building? This isn’t me. I live in a parallel universe. This place is light years away from hip.”

I finally reached the studio where two DJs, Chris T. and Meredith Ochs, introduced themselves. I took my place, guitar in hand, in front of a couple of microphones, then looked over at a computer screen where I noticed they had cued up a few Texas Sheiks songs to go with the interview. All the cued-up songs were cuts with other vocalists on them; none by me. My ever-vigilant brain interposed, “You see. This is the herd… moooo. What do you expect?”

Even though it was only two or three minutes before airtime, I asked Chris if he’d please change the tune selections to include my vocals. Busy doing other things, he acknowledged my request, but only half-heartedly — no eye contact. I wasn’t even sure he heard me. I thought to myself, “Oh gee, is this going to be a drag or what?”

Five, four, three, two, one... and we were on the air. Meredith gave the intro. I awaited her inane comments, but they never came. I could hardly believe my ears. She was on fire. She told her audience about Cambridge in the 60s, the Jim Kweskin Jug Band, Butterfield’s Better Days, albums with Maria, Amos Garrett, and on and on. Meredith knew a little something about my entire life. Then she mentioned that she and Chris played Stephen Bruton’s music all the time on their show. I took a few deep breaths. It felt like Meredith had just loosened my tie. I mused, “Take me, Meredith — just try to be gentle.” Then Chris chimed in, “...and Geoff, isn’t that the new Geoff Muldaur 00-18 Custom Martin guitar you’ve brought into the studio today? Beautiful. I see it has a slot head. I love slot heads. Don’t you? I have a couple at home.” I looked over at the computer. He had cued up all the right songs, and I never saw him do it.

Well, that was it! I fired my brain and I relaxed into one of the best interviews I’d had in a long, long time. Meredith and Chris really knew their stuff and they made it fun.

During that brief stay in NYC, I went to the Kandinsky show at The Guggenheim with my daughters Jenni and Clare. I, for one, love Frank Lloyd Wright’s Guggenheim building but not everyone does, or has. Peggy Guggenheim referred to the museum as “my uncle’s garage.” The uncle in question, Solomon R. Guggenheim, was an early collector of Kandinsky.

I’ve seen Vasily Kandinsky’s work in many museums, including the Lenbachhaus in Munich where he is on permanent exhibition as one of the Blaue Reiter (Blue Rider) group. None of the other members of that German art movement were in his league, unless one includes Paul Klee, a latecomer lured to the fold by Kandinsky himself.

Kandinsky creates worlds, each different. You wouldn’t know how different if you were to take a long view of it, as across the center space of the Guggenheim. One looks across from the other side and sees three or four very similar looking paintings. Then, upon walking around and taking a closer look, the works don’t look similar at all. They are very different — each its own cosmos. Kandinsky’s paintings are, for me, an example of the magic in Art. Why should those forms, colors, spaces arranged with such geometric playfulness produce such profound feelings to this viewer? That which might otherwise come off as cute – as is sometimes the case with Klee and Miro – becomes, in the hands of Kandinsky, transcendent. It’s a simple fact: The Kandy Man rules.

Vasily Kandinsky – “Composition 8” 1923

Probably my favorite aspect of the show was being with Jenni and Clare and knowing how much they enjoyed it.

Dad, Clare and Jenni at The Guggenheim

After NYC I headed up to the Boston area for a couple more gigs. With those behind me, I picked up a prime rib roast and a cooler; then drove to Logan Airport to pick up my girlfriend, Mary. After a night in a hotel in Cambridge, we loaded the rental car – cooler included – and headed down to Martha’s Vineyard to visit family and friends.

We stayed as the guests of Whit Griswold and Laura Wainwright. Whit and Laura live by the water on Lamberts Cove. It’s an idyllic spot (I’ve included pictures of the view from this place in a previous installment of “What’s Up”). Shortly after we arrived, Whit offered to take me out in his rowboat to fish for striped bass. There’s almost nothing I’d rather do, but it was not to be. My daughter Dardy had asked Mary and me to come see her new house and stay for a picnic supper. No contest — fishing was out. The meal had to be picnic-style because the house was under construction. It had just been framed out and closed in — still no flooring, kitchen, electricity, etc. But we had a great time. Dardy and grandson Quinlan (2 ½), showed us around the place before we all sat down for a quick – the sun was setting, light fading, uh oh it’s getting dark – supper.

Dad, Dardy and Quinlan

When Mary and I returned to Whit and Laura’s, we found out that, while we were gone, Whit had soloed his little boat up the north shore for a couple of miles, caught a nice striped bass and rowed back home. This is the stuff of heroes… zero ecological footprint… if you don’t count the bass and you eat it raw. Go Whit!

Striped bass fishing can become addictive. Many fishermen would rather fish for this species than any other. There’s really no way to explain it. It’s not the fight. Pound for pound, the striped bass isn’t a fighting fish like a bluefish, tarpon or members the tuna family. It’s an adequate table fish, but not outstanding like a mahi-mahi, black grouper or many of the flat fish varieties. But there is a mysterious aura to the “striper”. Its haunts are picturesque — along beaches, inlets and rocky shores, and it has a classic look about it. It looks like a fish ought to look. There’s a calm quality about the striped bass. It doesn’t go berserk when you land it — a few flops and it’s over. One can reach safely into its toothless mouth to remove a lure before placing it in the fish box.

Years ago, in the mid 70s and early 80s when I lived on Martha’s Vineyard, I did a lot of fishing, mostly for recreation, but I did some market fishing in the summer as well, and scalloped commercially in the winter. I balanced this – or tried to – with playing music on the road and recording albums. Friends would visit the Island from time to time, and customarily I would show them around, cook up a feast, maybe dig some clams or gather mussels, pull my lobster pots, go bird watching and, if it was the right season, go fishing for stripers. One summer during that era, my friend Steve Goodman showed up on the Island to play a club called the Hot Tin Roof.

I had met Steve back in the late 70s. He came to see Amos Garrett and me at a club in Chicago. Amos and I couldn’t get arrested in that town. The gig was a bomb. When Steve showed up, there was one lone customer sitting there waiting for the show to start. Steve came down the aisle strumming a guitar and singing, “There’s no business like show business, when there’s no-ooo business;” a nice introduction. He sure took the sting out of the evening and put smiles on our faces. Steve invited us over to his house the next day, and the more I got acquainted with him, the more I realized what a tough little guy he was. He had beaten cancer a few years back and was living life to the hilt. Steve was a ball of positive energy. His eyes seemed to bulge as if ideas were pushing to get out. He exercised a lot — 100 pushups, 100 sit-ups, etc. — this, way before it was popular. He had a bright and engaging wife named Nancy and three little kids, and he didn’t want to miss a moment of his life.

I saw Steve occasionally over the years, but most memorably, I visited him in the early spring of 1984 at a house in the Chelsea area of New York City. I was in town on my way home from Minneapolis where I had taken part in a music performance film called “The Survivors.” I’d come to New York looking for trouble — the bad kind — feeding my dangerous habits, up all night, quenching an insatiable thirst and putting who knows what into my body. I awoke one morning with a blaring hangover, head throbbing, unable to open my eyes from the piercing sunlight. I was sick as a dog, but for some reason I pulled it together to go see Steve. I had heard he was in town because his cancer had come back. Steve had been the poster child for Sloan Kettering a few years earlier, but he had recently returned for a check up, and that’s when he got the bad news.

I arrived at the house in Chelsea where Steve was staying and Nancy let me in. Steve was upstairs. I nervously waited for him to come down, nauseously pacing, sweating, ducking in and out of the bathroom to splash water on my face. Finally Steve appeared at the top of the stairs with his guitar. His head was bald with what looked like the bulb end of a turkey baster embossed into his skull, into which the doctors were delivering injections of chemo. He descended the steps in troubadour pose with a manic smile on his face, his jaw tightened. Then he strummed his way over to the round oak table where I was sitting and smashed his fist into the table with a primal scream, “Fuck!”

I remember thinking, “This guy has more guts in one of his little fingers than I have in my whole whimpering alcoholic body.” I felt a wave of shame come over me. He was fighting to hold onto his life. I was squandering mine. In a couple of days I went home to the Vineyard, had a couple more embarrassing binges and then sobered up — hopefully for good. Steve passed away later that year at the age of thirty-six.

Years before Steve’s sad ending, during that time on the Vineyard when he was playing the Hot Tin Roof, we had nothing but good times. I went to catch his show, and we chatted back stage where I found out that he’d be around for another day or so. A little fishing was in order. I kept my work skiff, the Jenny May, in a little fishing village “up Island” called Menemsha. I had discovered a nice drift on the outgoing evening tide that was almost certain to get striper action, so I asked Steve along. The next night, we were drifting in the boat. It was calm, starlit, with clear sounds amplified by the water; bell buoys clunking, the croaking of night herons, voices from shore and the slapping sound of screen doors. The tide was moving out at a good pace. Everything was perfect. Sure enough, halfway through the first drift, Steve’s line tightened up and he was onto a nice striper. Steve, being pummeled by instructions, stayed pretty cool. In a short time, he had his fish in the boat. Just to get an idea of how people react to catching this beautiful creature, here’s a picture of Steve later that night back at my place…

Steve Goodman with the “striper” he caught in Menemsha

Back to last fall. Mary and I had dinner with family (including sister Diana) and friends on the second night. A few local characters showed up and kept things interesting. I mean that in the best way. (I secretly aspired to local character status when I lived on the Vineyard.) The meal was delicious. I had brought that prime rib roast to the Vineyard just for this occasion, and although I overcooked it slightly, it was so well marbled that it stayed moist. The caramelized potatoes, carrots and onions – the delicious byproducts of cooking standing ribs – may have been the best part of the dinner.

Here’s a picture of grandson Quinlan with his dad, Sean (holding him), his grandpa, and some of his grandpa’s compadres. How can Quinlan go wrong with role models like this to show the way?

Quinlan with his Dad, Grandpa and the “Local Characters”

The next morning, Whit and I met up with our friend Soo Whiting to go bird watching. Soo is co-author with Barbara Pesch of the book, Vineyard Birds, a systematic list of birds seen on the Vineyard with their status, usual time of occurrence and their habitat. The book is a continuation of the 1959 Birds of Martha’s Vineyard by Ludlow Griscom and Guy Emerson. Incidentally, Griscom and Emerson were early bird watching heavyweights and pioneers of identification without the use of a shotgun, and mentors to Roger Tory Peterson.

I’ve known Soo forever and she is one of the best there is out in the field, not necessarily for her quick eyes and ears but for her ability to logically arrive at a safe identification — all the while offering guidance and encouragement to a career novice like me.

Later that day, Mary and I took a walk at one of my favorite haunts, a hidden cove at the end of Squibnocket Pond (which end I will not say). One must have a secret spot; a place where there is no time except for now and the only place is here and the only thing is this. We walked the edge of the cove for about… now times infinity.

The Author Holding a This (Horseshoe Crab)

That evening we wrapped up our visit by taking Dardy, Si and Quinlan to dinner.

We left the Vineyard the next day and I drove Mary to Logan airport where she caught a flight back to LA. I had a couple of days to kill, so I parked my rental car at the Providence airport and flew to Washington, DC to visit my dear and longtime friend Dorothy Jackson.

Dorothy was part of the Cambridge, MA family that I acquired in the 60s. Another member of that group, Paul Richard, moved to DC many years ago and became the art critic for the Washington Post. The three of us often get together when I’m in DC. This was one of those times, and the first evening Dorothy and I went to Paul’s for dinner with him and his convivial bride, Deborah.

At some point in the evening, we let Paul know that we would be going to the National Gallery the next day. He uncharacteristically suggested he come along because he wanted to show us an exhibition of Spanish armor currently on display. I mentally rolled my eyes (I hope it was just mentally), not being a fan of armor or the little peacocks that wore the stuff, but after all we would be going with Paul, so maybe things would get interesting.

We went down to the museum the next day and things did, indeed, get interesting. The armor show was called “The Art of Power.” We started walking through the exhibit and Paul, the keen observer, with acute historical perspective at the ready, began to call attention to details and curiosities. About halfway through the exhibit, a friend of Paul’s materialized from a panel in the room; actually a disguised door. His name was Mark Leithauser, Chief of Design at the National Gallery. Mark took us behind the wall to his offices where he and other masters of spatial logic concoct room designs for the museum’s exhibits. Dorothy tried on some chain mail around her head and neck. Being borderline petite she was just about the same size as those little guys who wore the stuff in times of yore.

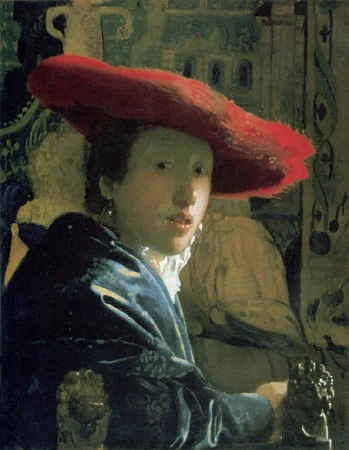

After our visit with Mark, we decided to get some coffee and swing by the museum’s collection of Vermeers on the way. These paintings are mandatory for any visit to the National Gallery. There are three and a half Vermeers in the collection (I’ll explain in a minute): A Lady Writing, A Woman Holding a Balance, The Girl With a Red Hat and Young Girl With a Flute. The first two are incredibly delicate and masterful works and testimony to the high quality of the National Gallery’s collection. The latter two are small pieces; the only works by Vermeer on wood panels. The first of these panels, The Girl With a Red Hat, is exquisite, sensuous and engaging. Young Girl With a Flute is awkward and confusing. It’s hard to believe that Vermeer did this painting, except that it says right under it: “Attributed to Johannes Vermeer.” The other three are labeled “Johannes Vermeer.” Something must have been going on with the attribution of Young Girl With a Flute among scholars of Dutch art.

We asked Paul about this. He knew about the controversy surrounding this painting but was shy on details. So, with questions still hanging in the air… just then, through the passageway from the adjoining room, walked Arthur Wheelock Jr., Curator of Northern Baroque Painting at the National Gallery and one of the world’s foremost authorities on Vermeer. Paul and Arthur go way back, so we were all introduced. I asked Arthur if he could please explain what was going on with The Girl With a Flute. He answered with a smile, “Do you have a few minutes?” Boy, did we.

Arthur told us that, as a young David E. Finley Fellow at the National Gallery, he had been the first to un-frame the two Vermeer panels. It was immediately clear to him that there was a qualitative difference between the two. Although the same paints had been used, at the same time, with similar techniques, there were telltale signs that Young Girl With a Flute could not have been painted, or at least finished, by Vermeer.

In The Girl With a Red Hat, Vermeer uses a delicate green wash under the red hat that gracefully curves around the face as if to invite the viewer into the painting. The same wash is used in Young Girl With a Flute, but it is applied more heavily and with less finesse, stopping abruptly on her chin. In The Girl With a Red Hat, Vermeer masterfully applied yellowish highlights to the girl’s blue robe creating depth and a plush look to the fabric. In Young Girl With a Flute the highlights are bland, the robe flat and dull. The subject in The Girl With a Red Hat is smartly placed with the highlights of her cheek and neckpiece centering the painting. The subject in Young Girl With a Flute is off to the side, left elbow out of the frame, and her rather plump and indelicate right hand cut off. Based on the position of her left forearm, her shoulder is impossibly low. Using x-ray technology it was found that the shoulder had once been higher (logically so) but was lowered to make room for her left earring.

There is more, but suffice to say there is enough wrong with Young Girl With a Flute to completely discredit it, were it not for the similarities in the pigments used, subject matter, the age of the panels, etc. Arthur Wheelock proposes with more than a little authority that Vermeer first painted The Girl With a Red Hat, then at some point started in on its pendant but laid it aside unfinished. He then died before finishing the second one. When the sale of his estate became imminent, a student or close friend finished off Young Girl With a Flute to get it into the sale. I’m buying it — the theory that is.

The Girl With A Red Hat

Young Girl With A Flute

Dorothy works for Campbell, Peachy & Associates, a firm that specializes in the coordination of special events in Washington. That evening we dined with Dorothy’s boss, Carolyn Peachy, and a young woman in town on business named Farouz Nishanova. Farouz is director of the Aga Khan Music Foundation in Central Asia. I didn’t know about this Aga Khan guy, but he’s definitely a big wig. His Highness (that’s a tip-off right there) is the spiritual leader of the Ismaili branch of Shia Islam who traces his ancestry back to Ali, a cousin of Muhammad.

The Aga Khan is founder of The Aga Khan Development Network (AKDN), an organization that focuses on the improvement of economic, social and cultural conditions in Asia and Africa. The cultural component of the Development Network is The Aga Khan Trust for Culture, and within that is the Aga Khan Music Initiative in Central Asia of which Farouz is the Director. Whew!

Farouz is one of over 60,000 employees of the AKDN. The network has an annual budget for non-profit development projects of $450,000,000 in 25 countries. By contrast the United States National Endowment for the Arts shells out a measly $140,000,000 a year. Single cities in Europe spend more annually on their local cultural activities than the United States spends nationally. This year, Vienna, Austria alone will spend $330,000,000 on cultural affairs.

Farouz’s organization works to preserve, and in some cases revive, the musical heritage of Central Asian countries. For example, when the Taliban took over Afghanistan in 1979 they outlawed music. Today the Music Initiative’s organization provides musical instruction and performances in Kabul and in the old city of Herat and even operates a center for instruction in the making of traditional instruments. Farouz talked about the music of Kazakhstan, Kyrgystan, Tajikistan, etc. If it ends in “-stan” Farouz and the Music Initiative are there. It was so refreshing to hear her talk. I had never heard of any of the great musicians she works with or any of the instruments they play. Performers like Jonboz Dushanbiev, Homayun Sakhi Alim Qasimov and Nurak Abdurakhmanov. Instruments like the Ghijak, rubâb, morin khuur, dombra or dutar. Thankfully, this is still a big world.

The next day I had to get back to New England for a couple of gigs. Adieu to Dorothy and her interesting friends. I had a long day and night before me, because after I landed in Providence, I would drive a couple of hours north to my gig. Then, after the gig, I would point the rental car towards New York and drive to a motel outside of New Haven where I would be in position to get to NYC the next morning to shoot a video for Stefan Grossman’s Guitar Artistry series. This I did. All went well, and after the shoot, I drove up to my old hometown of Woodstock, NY. That evening I got together with my good pal John Sebastian and his wife, Catherine, for an easygoing — it’s always easygoing with John — Italian dinner. After dinner I drove up into the hills for a good night’s sleep at the empty getaway home of another friend who was kind enough to let me use it. I needed to hear the wind in the mountains and the sounds of the woods and fill my lungs with cool, crisp air. I slept long and deep that night.

The next morning I awoke refreshed and ready to go. I left the Woodstock Mountains and headed to Boston. There I would catch a flight to Amsterdam, where I would meet up with Jim Kweskin for a tour of Northern Europe.

When I arrived at Amsterdam, Schiphol the next day, I started to get that warm feeling that always comes over me when I return to civilization. The weight of stress that one carries around with them in my faltering country begins to lift. I was in Amsterdam, in Europe, where people are still living the American Dream. Amsterdam — hipster heaven, live and let live, Peace Brother! My sense of comfort was due in part to the fact that I would be reuniting with my honorary Dutch Family, the Steultjens/Miedema clan: Peter Steultjens and his wife, Jitta and daughter, Liza; also Jitta’s sister, Alet Miedema and her son Arlo. Alet and Peter met me at the airport and drove me to my hotel near the Paradiso, the venue where Jim and I would play in a few days. Jim and his wife, Sofie, would arrive the day before the gig. First, however, I would enjoy Holland and spend a little quality time with my “family”. It felt so good to be home. I had an easy interview with a writer in my hotel room, ate a little dinner and got some shuteye.

The next day Peter and Alet came over to get me and we drove east to the Kröller-Müller Museum, a little-known European art treasure trove. Helene Müller was the daughter of a German industrialist. She married a Dutchman, Anton Kröller, who eventually became a director of her father’s company. We are talking about big bucks here. Helene became interested in collecting while studying art appreciation with art critic and collector H.P. Bremmer. She soon engaged Bremmer as her personal advisor and together they acquired nearly 11,500 objects.

During the 20s and 30s, however, the fortunes of the family enterprise began to dwindle. Fearing the loss of her art collection, Helene made a deal with the Dutch government to donate it to the Netherlands. In return, the government would house the collection in a museum to be located on her estate near the town of Otterlo. The Kröller-Müller Museum is now situated in the center of that estate, the National Park De Hoge Veluwe. It’s a beautiful wooded area with hundreds of acres. Parking is at the perimeter and one either walks or bicycles into the park and museum.

Helene Kröller was particularly excited by the work of Vincent Van Gogh and thus collected 91 of his paintings and 180 works on paper. In addition, the museum includes works by Mondrian (an entire roomful), Corot, Courbet, Cézanne, Picasso, Braque, Seurat and Bart van der Leck (a new one on me) among many others.

After the Kröller-Müller we headed to the little town of Heerde for a visit with Wim van de Weg. Wim is a banjo aficionado who buys, sells, trades, sets up and – thankfully for me in this case – loans banjos. Jim and I needed a 5-string banjo for our tour, and somehow Wim turned out to be the guy to ask. He was happy to accommodate us. Wim runs a trucking company and lives in a nice home at the end of a rural road with a garden, fruit trees, barn, and a little instrument shop. On the wall in the shop are banjos of all descriptions.

Wim van der Weg’s Shop

Wim’s wife, Willemien, met us first and welcomed us into her home. We weren’t the only visitors. Willemien’s daughter dropped in with her ten-week-old daughter, snuggled up in a beautiful white hand-knit body suit. Willemien’s mother was there too, making it four generations on the premises.

Then Wim showed up. He’s a cool customer. It took a while, but after tea and cookies in the kitchen area and a little conversation Wim’s friendliness and dry wit surfaced. “What do you get when you drop a banjo down a mineshaft?” he asked. Silence… then he answered himself, “A flat miner.” I felt a bit sorry for Willemien. She married Wim before he became obsessed with banjos — and banjo jokes.

Wim Showing Geoff one of his Banjos

After a tour of the shop and the garden it was time to drive back to A’dam. After a full day, more sleep was indicated. I don’t think I did anything that night except eat and hit the hay.

I awoke the next morning to a beautiful sunny day, had breakfast, and then met Alet downstairs. We walked the streets of the city, over and along the canals to the Amstel River. There we found the Hermitage Amsterdam, a museum that exhibits objects solely from the Hermitage in St. Petersburg. They call this arrangement a “dependency.” On this day they were exhibiting royal clothing and objects of the Tsars. It was called “At The Russian Court.” As we walked through various reconstructed palace rooms with manikins all decked out in the garb of rulers, I became more and more uncomfortable. Then we came upon a huge, framed portrait of Tsar Nicholas II decked out in a luxurious white coat with oversized epaulets, his chest pretentiously bulging with medals and ribbons. Almost immediately I felt like blowing the bastard’s head off. There was just something about the guy. Based on the accounts of his proper demise, I knew I wasn’t alone in the way I reacted. I asked Alet if we could please leave.

This was the day that Jim and Sofie arrived. I gave them a little time to settle in, but, because the weather was so spectacular, I urged the two visitors overcome their jet lag and hit the streets of Amsterdam with me for a long walk. It was great to be with Jim and Sofie under such good circumstances and to see them get as wide-eyed as I was about Amsterdam. When we got back to the hotel, a young couple was waiting for us. Guitar player Titus Vollmer and his wife, Paloma, had just arrived from Bavaria. They were friends of Jim and Sofie. When Titus and Paloma, independent of each other, attended the Berklee College of Music in Boston, they ended up as part of a group of students renting a house from Jim and Sofie. It was in that house that they met and fell in love, so they must associate Jim and Sofie with meeting and falling in love. At least it looked that way when they began hugging on the street outside the hotel.

Later that evening, the Miedema ladies, Jitta and Alet, came to get us at the hotel. We all walked to a traditional Dutch restaurant called Het Zwaantje. There we squeezed ourselves into a cozy little booth where we were soon joined by the restaurant mascot, a large white cat named Minoes. Minoes seemed more interested in love than food. Het Zwaantje had so much atmosphere I would have been happy with mediocre food. But the food was not mediocre. It was delicious. This was a very special experience — something an American, or even a Bavarian tourist would not know to do. This is why it is so important — and, indeed, I am so very fortunate — that I have a Dutch family to ensure that my time in Holland is very special. I recommend to all those spending a good bit of time in Amsterdam to find a Dutch family of your very own. You won’t regret it.

The next day Peter, Alet, Jim, Sofie and I headed east to an old wooden windmill near the town of Bemmel. We had been in anticipation of this for some time. There we met up with my friend, Jan Meurs. I’ve played for Jan in the past for a music series he runs in Bemmel. When he is not promoting shows, Jan is part of an organization that provides constructive activities for the intellectually disabled. With the help of the local government, they’ve set up a shop next to the mill. There the workers package the mill’s flour, which they sell along with other items they make and assemble. I’d been to the windmill before with Jan, but I really wanted my friends to see this place.

The Mill Near Bemmel

The mill owner who sold (or perhaps leased) the mill to the town for it’s beneficent use is Gert van Ede. Jan’s organization will be taking over the operation of the mill sometime this year, but until then Gert is in charge. He comes from a long line of mill men, and he runs the windmill like the skipper of a sailing vessel. Everything seems within reach for him. At nearly eighty years old, he climbs the rigging with ease, every movement economical and seemingly effortless.

It’s interesting to watch the body language between Jan, a “live and let live” liberal and Gert, a staunch conservative. Gert’s a military man all the way. On weekends he drives vintage tanks for recreation. In his eyes, America can do no wrong. They saved his country and that’s it. As a young boy, he remembers sitting with his father on the top deck of this very mill watching the allied forces parachute onto the battlefields of nearby Arnhem. Jan is anything but a military man, but he’s very fit — a pacifist tough-ass. He wears wooden shoes and walks with an athletic, graceful motion. Jan seems to enjoy calmly provoking Gert with words of peace, and he gets away with it. Something tells me they respect each other, which to me would be quite understandable.

Jim and Geoff Climb the Sales

After returning to Amsterdam that evening, I freshened up at the hotel, then met with Alet, Peter and Jitta and walked to the Concertgebouw for a performance of Mahler’s Third Symphony. I go for Mahler, but I didn’t go for this symphony. Man, was it long — his longest; 104 minutes (by my watch) with no break — a butt-numbing musical smorgasbord. Even so, I loved just being there with my friends in that renowned concert hall with it’s rich, full sound.

The next day, Jim and I actually had to play a gig (this can happen). It was a Sunday afternoon gig in the small room of the Paradiso. Finally Jim was to experience the wonderful Dutch audience I’ve come to love. Our driver and tour manager, Gerrit Brockmann, arrived that day from Germany with a van; we threw our instruments in and made it over to the venue. Thanks to a very positive preview in de Volkskrant (the interview I did the first evening), the place was jammed with smiling faces of all ages. Titus sat in on a few tunes and he smoked them — everything clicked.

After the show, we all went over to Peter and Jitta’s home for a delicious catered dinner. It seemed a very posh thing to do. So, I asked Jitta, “How can you afford this? It’s so extravagant.” Jitta answered, “Oh, no no, not to worry, it’s paid for by the Dutch government. In Holland we have single-payer catered dinners.” “Wow”, I said, “Are you lucky! In the USA we have to pay for catering.”*

To top it off, Liza made a chocolate cake; very dangerous to eat, but I took the risk. After a little picking and singing in the kitchen, mostly by Jim and Titus, we said our goodbyes and headed back to the hotel. Bye bye, Dutch Family….

* This exchange did not occur.

Arlo, Alet, Liza, Jitta and Peter

The next morning we headed off to Northern Germany in the van with our trusted driver, Gerrit. The first stop was our home base, Bremen, where we stayed at my favorite little hotel, The Schaper Siedenburg. Nothing too fancy, but it’s near the Hauptbahnhof (main train station) and it’s only a short walk to the aldstadt (old town). This is the hotel where Radio Bremen has for many years housed jazz and blues musicians. It’s got the vibe, and it’s also got a great German-style breakfast buffet. Most importantly, on the front desk there is a sign that says, “Trust The Girls”, and I do. They really take care of their guests.

Jim and I played a gig shortly after our arrival in Bremen at a club called Moments. I’d made a live album there a few years back. It’s a nice enough place, but the audience is difficult. Bremen audiences hold their feelings in their hearts, and although they may enjoy the music very much, they are reluctant to show it. When they applaud, you can count the number of claps with the fingers on one hand. It can be a shocker the first time around, which it was for Jim. I warned him, but no amount of warning can prepare a performer for this phenomenon. After our love fest in Amsterdam with the garrulous Dutch, this gig was very tough. The audience was typically quiet, the lights were blaring in our eyes, we couldn’t hear ourselves, etc, etc. The result was a stiff show with lots of mistakes. No excuses though — this was probably an experience we needed. It would be our only difficult show on the tour.

The next day we headed east to Hamburg and things were very different. We played a club called Fabrik, severe in appearance but well run. I’d been there before. The audience was small, but they were very much easier than Bremen and the sound was perfect. Anja Rittmoeller, my artist liaison from Deutche Grammophon, showed up. This was a treat for me. She was essential to the making of my Bix Beiderbecke tribute album, Private Astronomy, so I am eternally in her debt. With our performance at Fabrik, Jim and I began to get back in stride.

The next night we played back near Bremen in the town of Stuhr. The show was part of a series presented in the Rathaus (city hall). The presenter, Edgar Woeltje, had everything in order. He’s done this for quite a few years and he’s got it down. The townspeople have come to trust him. So, although you are not playing for hipsters, you are at least playing for willing victims. We had a great night, ending with a good Italian dinner at a restaurant called Sausalito. Edgar had called ahead to ask if they would stay open for us after hours. They did, and the food was delicious. Thanks, Edgar.

The next day we flew to Stockholm, Sweden, where Jim and I were to play a show, teach guitar and do a little sightseeing. We stayed in a comfortable apartment in the city courtesy of our host, Lasse Johansson. Lasse is the fellow who invited me to play at his guitar camp in Hungary last summer, so it seems every time I see him and his sweetheart, Ágnes, it is for something very special. I’d also played and taught in Stockholm before so I knew how nice this would be. Now Jim would get a taste of the guitar picker scene that Lasse has built up over the years in that beautiful city. He would also get to hear Lasse’s terrific finger picking.

It was raining the next day but nonetheless Lasse picked us up for a little sightseeing. We drove up to a restaurant overlooking the city….

Stockholm

From there we went nearby to the Folklore Centrum for a visit with Izzy Young. Stockholm has been Izzy’s home since 1973 when he left Greenwich Village, never to return. In the Village, Izzy was the proprietor of The Folklore Center on MacDougal Street; a meeting place for the folkies of the 60s. Jim Kweskin used to hang out at the store when he was playing down the street at the Gaslight Café with Bob Dylan, Peter Stampfel and Sandy Bull. So Jim knew Izzy and Izzy knew Jim. They reminisced, and reminisced, and reminisced…

That evening Jim and I played a venue called Stallet, where I had performed the last time. And just like last time, it was a terrific night with an appreciative audience. Izzy showed up, which I understand is a rare occurrence. It seemed to mean a lot to him to see Jim again.

Geoff, Izzy and Jim in Stockholm

The next day we had our guitar workshop. As I said, Lasse has quite a bunch of accomplished pickers in that town. Some of these guys had come to Hungary so I knew them — Anders, Cliff and Tomas. Bert Deivert, an American ex-pat and an old busker pal of Peter Case, was also in attendance. This group of students is very focused. They work at it, and they get it. They demand the teacher’s concentration as well.

As it is a tradition of this group, halfway through the day we took a break from the workshop and went to the Museum of Modern Art for lunch. To get there, we walked along the harbor with its square-rigged sailing ships, tugs, pleasure craft and tenders, then across a scenic bridge, and up a hill to the museum — a refreshing break. The food at the museum is good too.

Geoff & Jim on the Way to The Museum

We went to work again in the afternoon, eventually splitting the group in two. I taught one half of the class my arrangement of “Just a Little While to Stay Here,” while out in the hallway Jim taught the other half a harmony part for the song. When Jim and his guys returned we played the arrangement and it sounded great. This is a rare bunch…

The Guitar Workshop in Stockholm

That night we ate at an old traditional Swedish restaurant and the food was very good. But I must say, Swedes just can’t stuff cabbage the way those folks in the Middle East do (just my opinion). It was good, though. Afterwards, back at the apartment, Jim and Lasse got down to the business of guitar picking and trading tunes. Bert sat in, and I may have strummed a few. But when Lasse Johansson and Jim Kweskin are picking, the angels appear. These guys were born to play guitar.

The next day, Jim, Sofie and I hopped a train for Göteborg on Sweden’s Southwest coast. We had a gig that night a little north of there in a town called Uddevalla. It was a beautiful, crisp fall day when we pulled out of Stockholm. The train traversed seemingly endless flatlands with farms and brick-red wooden barns. White cattle were in the fields with magpies, crows and the occasional grey heron. There was little else in the way of birds save a few little tweets hopping about, difficult to distinguish from a moving train. Occasionally there were patches of birches, then aspens with their yellow-orange fall foliage, then a stand of young evergreens. Owl habitat?

The train was comfortable, the ride smooth. We settled in for an easy journey… and then… [warm orchestral strings, La Boheme, Mimi is climbing the stairs to Rodolpho’s garret]… lo and behold… [strings ascending with clarinets]… she appeared... [strings higher, higher!]… the “Conductor From Heaven!” She was stunning; perhaps the most beautiful woman alive. I couldn’t believe my eyes. How beautiful was she? To put it in a semi-Swedish context, this young woman made Greta Garbo look like Margaret Hamilton. No screen test needed. Roll film, a star is born. Yet she was our conductor. How could this be? As she made her way up the aisle, I knew she would soon punch my ticket. I waited.

Time passed — how long I do not know. Soon, I looked at my ticket. It had been punched. I sat there in a daze, looking out the window. The scenery came slowly into focus. As we drew nearer to the western coast, I could see a change in the landscape. There were now areas of soft, rolling hills. It was if the land were a rug that had been shaken out and laid flat, with some areas still bunched up, perhaps the remains of a glacial retreat.

In time, the train pulled into Göteborg and we disembarked. As we stepped onto the platform, I could see the “Conductor From Heaven” talking to a few passengers. I walked over and waited my turn. Soon our eyes met. I thanked her and told her that I doubted very much I would ever again meet a conductor as beautiful as she in what was left of my empty life. She smiled at me warmly, and I could not detect a shred of pity in her look.

We were met at the station by Anders Olofsson, a member of the Uddevalla Bluesförening (blues society). From there, we drove north along the coastal highway that eventually crosses the border with Norway. When we arrived in Uddevalla, we met our presenter, Jan Gustavson who helped us get settled in our hotel rooms, and then escorted us to a buffet lunch downstairs. Jan was immediately likeable and it seemed like we were going to have a good time later that evening. Lunch looked Scandinavian; unidentifiable pickled fish, dumplings, sour cream and chunks of brown meat. Wow, tough choice. I really didn’t know what to put on my plate. Fortunately, Jan was there to help. He recommended the blueberry herring; then he recommended the mustard herring; then the herring cake…

We played that night in the Bohusläns Museum, a modern building on the edge of the Bäveån River, which flows through Uddevalla. We were given a nice dressing area, plenty of good hospitality and soon we were ready to go. People of all ages were in the seats, including a crying baby; a lucky opportunity to ad lib. They ate us up, which inspired us further — you know how that goes. Jim and I nailed it pretty good, thanks to that audience.

After the performance, we went across to the other side of the river and boarded a cruise ship. There, some nice folks had pulled together a little after-gig dinner for us. We ate in the crew’s galley below decks — very snug and special. Our companions around the table were our presenter, Jan Gustavson, another man named Jan who co-skippered the boat, his girlfriend, Eva, and the other skipper, Christian Gjedrum. Now there’s a name for a seafaring man – Christian. It was he who rustled up the delicious chicken, potatoes and salad.

There were stories. Skipper Jan had been a fisherman on the Baltic, but the fish population there had dropped so much that he had had to find other ways to keep his sea life going — hence the cruise ship. We talked about salmon and cod stocks. I can’t quite remember, but I would not be surprised if we also discussed the herring population. There was some talk about rich Norwegian tourists as well.

It’s funny. When we were in Bremen, as visiting Americans, the prices were a little high for us. We had to keep an eye on what we were spending and by all means not confuse euros for US dollars. But Swedes come down to Bremen on holidays to go to festivals and purchase goods because, for them, Germany is so inexpensive. Swedish kronor go along way against the euro. But here at dinner on the cruise ship, we were told that the Norwegians come down across the border from Oslo to carry on and buy goods in Sweden because, for them, it is a bargain. Norwegian kroner are worth more than the Swedish kronor. You get the picture. It’s a food chain. Norway is a small whale, and the US is a haddock.

We could’ve chatted forever, but the three visitors needed to get up early for the drive back to Göteborg and a flight to Bremen the next day.

This we did, and after a strenuous trek across the Frankfurt airport to make our connecting flight, we arrived back in Bremen in the afternoon. I was in luck. Due to the generosity of Radio Bremen, a backstage pass was waiting for me at Die Glocke, Bremen’s highly acclaimed concert hall. It was to be an evening of Ravel by the Bremen Philharmoniker Orchestra. I got down there early and was shown to an exclusive booth above the stage. I could almost read the cello parts from my plush seat. This vantage point was very different for me, and very educational at that. The booth was also reserved for the soloists, so when they finished up I got to meet them and whisper questions.

Le Tombeau de Couperin was first on the program, then Ravel’s Piano Concerto for Left Hand with soloist Eric le Sage. The piece was commissioned by Paul Wittgenstein, a wealthy concert pianist from Vienna and brother to well-know philosopher, Ludwig. Paul lost his right arm fighting in World War I. It’s amazing to me what happened after that. He was captured by the enemy, and after spending months in Russian concentration camps, where rampant disease and rat infestation often lead to insanity or death, he got back to Vienna. There, he soon tried to re-enlist. Was this guy nuts? Imagine risking one’s life for a family, the Habsburgs — not even a country. Heaven must have seemed so real back then. In any case, having the resources to do so, he commissioned piano works for left hand by composers such as Richard Strauss, Korngold, Prokofiev, Hindemith, Britten and Ravel.

With Ravel, the master orchestrator, there are so many “effects” to wonder about. During the performance, I would hear a strange, shimmering sound for instance and then look quickly around the orchestra trying to catch the perpetrator(s) in the act. At times, I couldn’t keep my eyes off the tiny contra bassoonist, Hiroyaki Yamazaki. She changed reeds constantly. On the break, I asked a couple of the other bassoonists why she did this (remember I was in a backstage booth) and, for some reason, they didn’t notice that she, in fact, did. Perhaps there are very few performances each year when the orchestra requires her services. In any case, through translation, I got my answer from her through them. If she had time she would attach the correct reed for each particular passage — one that played a key note or series of notes particularly well.

Le Sage was terrific. I remember him most for his encore, a short solo piece by Schumann. I need to hear more of Schumann’s piano pieces.

Hamburg violinist Anette Behr-König was the next soloist, playing Tzigane-Rapsodie de Concert for Violin and Orchestra. She was poured into a form-fitting, flaming red satin dress with gypsy-like black embroidery — a bold fashion statement at the least. Tzigane is a virtuosic piece with passages conjuring a romanticized gypsy life. Anette was rough on that little violin, passionately digging into each note. I thought she was going to break the instrument. The first couple of minutes were played entirely on the low g-string of the violin, giving it a raw, authentic tone reminding me of Taraf de Haidouks.

We had a couple of days off in Bremen that were actually a little boring, although we all got to shop, do laundry, have a couple of nice dinners and, in my case, take long walks along the “Wallgraben,” an elongated lake that was originally a moat for the old city of Bremen. This area became the first city park in Germany. Mallards, common gallinules and little gulls kept my attention during the walks.

Time to work again. Jim and I had a nice gig up in Bremerhaven, then played a place called The Jazz-Club in Hannover. My Munich friend, Carl-Ludwig Reichert, stopped in on us, having made a detour on his way home from a conference in Berlin. It was great to see Carl-Ludwig, but also to play for him. He had come out of his way because of his respect for Kweskin and his music. I could see him in the audience, focusing, listening intently. We hit it pretty good, so I don’t think he was disappointed.

Another visitor to the Jazz-Club that night was journalist Bernd Gürtler. He had come all the way from Dresden to interview us (7 ½ hours by train) so we gave him as much of our time as we could. Bernd didn’t know it, but I had just made arrangements to fill a couple days off by going to Dresden, so we made plans to meet up when I got there.

Jim’s last gig for the tour – I would do a couple of solo dates before coming home – was in Oldenburg. This gig was different. We played for a folk society in a room called Gasthof Mueggenkrug. It was reminiscent of a VFW hall. That night one would have expected a raffle of some sort rather than a concert. But there they were, the townsfolk, ready to do their best to enjoy what our host, Niko, had cooked up for them. Niko has headed the folk society in Oldenburg for 31 years. He seems to be Oldenburg’s link to the offbeat. As in Stuhr, the audience was open and willing and, as in Stuhr, Jim and I had a real good evening due in part to that fact.

After the show we went over to Niko’s for an almost ceremonial dinner of traditional food. Niko’s house was dark and mysterious, full of items that would have taken forever to explain. I knew we had to drive back to Bremen that night so I started to wonder what the heck we were doing there.

Then Niko began to tell us a story. He passed out pewter spoons and asked us to hold them in our left hands. Slowly, in broken English, he told us about the ditch diggers who worked on the dykes 1,000 years ago in the Friesan area of Northern Germany, of which Oldenburg is a part. Their right hands would’ve been too tired at days end to hold onto the spoons, so this traditional rite honors those workers by using the left hand. He then poured schnapps into the spoons (soda water in mine). When schnapps is served in this way it is called “Clear Words of God.” Then we partook. This was very nice, but I was still scratching my head and wondering when we’d get back to Bremen.

Soon a little food came to the table, Gee, herring! Wow, different kinds of herring! Then potatoes, good. Everything was proceeding at a snail’s pace. At this rate, we wouldn’t get home until dawn. My anxiety increased. Then something happened. Niko started to tell us about his life. As soon as I calmed my mind and allowed myself to be there and listen, I finally knew why we had really come to Oldenburg. Time became less important.

With his thick accent it was difficult to get every word, but he told us about his family. Niko is Ukranian. He and a few family members came to Oldenberg after the war. I can’t remember the details, but a slight name change was necessary to lessen suspicion of their origin. During the war, the Nazis had murdered most of his family for aiding Jews. Those who survived somehow wended their way to northeastern Germany. The family troubles went back to World War I, with similar tragedies at the hands of the Bolsheviks. Niko’s grandfather had been a partisan in both world wars; first fighting the Bolsheviks, then the Nazis. So here we were in the home of a survivor who’s painful memories were enshrined in his dark and cluttered home. Niko gave us the pewter spoons as mementos. I’ve put mine in a safe place and I’m grateful to have it.

The next morning, Jim and Sofie left Bremen for The States. Later, Gerrit came by the hotel, picked me up and we drove south to the town of Lich for a solo performance. The building I played in was a restored synagogue where, during the month of May each year, the town sponsors a festival honoring the Jews. I played to a polite, provincial audience. Hard to tell, but I do think I got inside a few of them.

After the gig we ate in an Eritrean restaurant called Savanne. The food was delicious. Interestingly, the African family that owns the restaurant had been invited to the town of Lich from Frankfurt. The family had lost their lease in the big city. How lucky for them that some nice folks from Lich heard about this and asked them to open their restaurant next to a movie theatre in town. The restaurant was buzzing and full of young people. The good news: no hand-held devices. The bad news: a lot of smoking out on the patio.

The next day, Gerrit drove me to Kassel where I caught a train east towards Dresden, a major center of the GDR during the period of communist rule. There was a stop along the way where I had to change trains. In order to see if everything was in order with my ticket, I decided to ask the conductor to take a look. Then I saw the conductor coming through the sliding door into our compartment. My goodness — the conductor was a very attractive young woman. Coincidence? Serendipity? I showed her my ticket and asked if everything was okay for my transfer. But she seemed put out by my request — dismissive and aloof. “Well, Margaret,” I peevishly thought to myself. “I know a conductor up in Sweden who, unlike you, is very accommodating and pleasant.”

I got into Dresden and found out that my hotel was only a short walk away from the hauptbahnhof. It was also well situated for walks into the aldstadt (or more accurately, the re-creation of the aldstadt) and to the Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister, my main reason for traveling to Dresden. This museum is home to two Vermeers, The Procuress and A Girl Reading A Letter By An Open Window. That evening I took a walk and had dinner in the hotel — braised beef with red sauerkraut and potato puff. Very good.

The next morning I headed over to the Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister, one of the buildings in a palace complex known as the Zwinger. The entire area was magnificent. The Zwinger and the surrounding buildings were originally the digs of Augustus the Strong. Now there’s a name. Augustus II was, indeed, reputedly strong, but more famous for his patronage of the arts and for establishing the city of Dresden as a cultural center of Europe.

I entered the museum, went right upstairs, and the Vermeers were there. The earlier one, The Procuress, was vibrant and captivating. I didn’t expect this because the early Vermeers — although earlier by only a year or two — are not necessarily my favorites. But in person, this painting had it. It depicts a few sleazy, leering upper class rowdies paying a madam for a little action from one of her professional associates. Directly behind her is a man in a red coat, his left arm over her shoulder and his very large hand groping her bosom. Could Vermeer have used the same model for this fondler that he used in The Geographer? Or was there a Delft gene for oversized male left hands?

The other Vermeer, A Girl Reading A Letter By An Open Window, was disappointing. Untypically, reproductions I’ve seen of this beautiful painting look far better than the actual work. I was confused. I walked downstairs into the museum bookstore and asked an employee – who probably expected a question regarding a book – a very direct question. “Are some of your paintings dirty?” Her eyes dropped; then she turned her head away, as if to say, “I didn’t hear that,” but then she slowly raised her head, looked around cautiously and quietly said, “Yes.” I sportively suggested that the museum hire some smart Italians to come up to Dresden and do some restoration work. She then explained that under communism, nothing was ever maintained properly — the buildings, artwork, and historical records. The Russians left in 1989, so it’s only been a little over 20 years that Dresden has been rebuilding. In any case, they will begin to restore the paintings in the Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister this year. Glad I asked.

In addition to the Vermeers, the museum was loaded with exceptional art — Durer, Cranach (the best I’ve ever seen), Botticelli, Massys, Mantegna (“The Holy Family” wow), Rembrandt, Velasquez, a precious portrait of a young woman by Gerard Dou, a Millet that seemed to anticipate Cezanne’s view of things. There was too much to see. I couldn’t take it all in. I must have O.F.S. (Optic Fatigue Syndrome. Is there a drug for this? Ask your physician.)

Jan Vermeer – The Procuress

Jan Vermeer – A Girl Reading A Letter by An Open Window

I also stopped in at the Städtische Galerie. Not much caught my eye, but there was a very nice Otto Dix self-portrait and a stunning painting by an artist named Richard Muller of a nude male model posing for an artist in a large atelier.

On the walk back to the hotel, I stopped in for late lunch at a place called Gänsedieb (Goose Thief) Restaurant. The restaurant was named for a statue outside its doors of a boy holding a goose, or for the folk tale connected with the statue, but I never found out what it was. I had some traditional Saxon potato soup with little wieners in it — very tasty. The menu also offered “1 Becher Gänsefett” (one cup of goose fat), or if you’d rather a little take out, Gänsefett Zum mit Nehmen (goose fat to go). Then, of course, there is the standby, goose fat on toast. Mmmm, gute.

Later that evening, I met up with Bernd Gürtler — the journalist who interviewed Jim and me in Hannover — and his wife, Petra. Our plan was to have dinner near the River Elbe. We strolled through the aldstadt and I took the opportunity to ask them about life under communism and the changes since reunification. The long and the short of it seemed to be this: The city looks better now and there is easier access to information, but one has to work harder.

Regarding access to information during the Soviet occupation, Dresden was famous for having an uninformed population. Unlike other locations in East Germany where inhabitants could figure out ways – though illegal – to watch West German TV, the city of Dresden could not. It is situated in the low-lying Elbe River valley, a topography that made West German TV reception impossible. Hence it acquired the nickname, Valley of the Clueless.

We continued our walk towards the river and on the way came upon the Procession of Princes, a long wall of mosaics depicting the rulers of Saxony from 1127 to 1918. Once again, these guys had names you could chew on — Albert the Bear, Henry the Fowler (“w” not “u”), Otto the Illustrious, and the main man himself was there, Augustus the Strong. Come to think of it, we should adopt this naming convention in my country, with names like, Stanley the Aggressive, Ashley the Vapid, Marty the Short Seller. Or Mary’s favorite, Geoff, The Interrupter.

Right near the river was our destination, a restaurant tucked against the riverbank near the entrance to the Augustus brücke (bridge). The wholesome aroma of home cooking met us as we entered. I already loved the place. There was a soft amber glow to the interior imparted by all its wood surfaces. The sound of the patrons was mellow and unobtrusive; soft mumbles and murmurs. I had the pork sauerbraten; Berndt and Petra had the perch, and we talked and talked and talked. I really enjoyed their company. After a stroll back towards the hotel, we said our goodbyes. I hope to return. In a few years, the city will have been rebuilt and quite glorious, and the people of West Germany will still be grumbling about having paid for it.

The next day I caught the train to Bremen, via Brunswick. I had no idea we would be stopping at Brunswick or I would’ve planned to visit the Herzog Anton Ulrich Museum. How frustrating: they have a Vermeer. I could’ve scored a three-fer, more reason to return to this area.

After getting back to Bremen I had two more solo gigs to go… one in Göttingen and one in Northeim. The gig in Northeim was less than memorable, but the one in Göttingen was terrific, if not unique. I played in a little storefront called Kim. They sell used items there — clothes, books, lamps, you name it. By the time I arrived, the women who run the place – Vera, Christiana and Birgit – had transformed the store into a small performance space for my show. They all made me feel like I had just come home. This may have been the smallest space I’ve ever played, but the hearts of all those involved, including the audience, were large. A nice fellow named Jörg Bachmann promoted this and the show in Northeim.

The day after the Kim gig, I visited Gerhard Steidl at his printing house in Göttingen. Steidl, as the firm is simply called, produces high quality books on fine art, fashion, photography, etc. My friend John Cohen is soon to publish his Peru photographs with Steidl, and the company has thus far printed four volumes of the Ed Ruscha Catalogue Raisonné of Paintings. As you may know, Ed created the cover art for the Texas Sheiks album released in September ‘09. It’s through this connection with Ed and his brother, Paul, that I had the pleasure of touring Steidelville — the building’s nickname — and having lunch on the premises with Gerhard and a few other guests. Chef Rudi cooked up some deliciously fresh fish — lunch break haute cuisine.

The tour was very impressive — modern presses, skids full of the finest paper, high-end Macs for image control and composition, and on and on. I never saw one person in the place leaning on a broom. Of course I was walking through with Gerhard, but I suspect that everyone working there is dedicated in the extreme. Steidl (the man and the company) does not mess around. This is the highest quality printer on the planet — and the best place to eat in Göttingen if you can get a table.

Okay, that was it. It was time to drive back to Bremen and fly home to the USA. Auf wiedersehen…

After a few days back home in LA, life began to pick up again. Jim Kweskin and I played Tucson and Albuquerque; then did a very nice local gig at Whittier College in nearby Whittier, CA. By the way, a local gig in LA can be up to two or three hours away. I call it local if I’m able to sleep in my own bed that night.

During the period right up until the end of the year I spent a lot of my time promoting the new Texas Sheiks album. A week or so after Whittier, I had my first interview with Terry Gross on National Public Radio. I wondered over the past few years why Terry had never interviewed me, but I found out it was not for lack of knowledge about my work, or me. We discussed the new Texas Sheiks album and Terry played a little catch-up on my life and career. I liked her. Something clicked. She listened, and she responded spontaneously. She also seemed genuinely interested in what I had to say. This is her gift.

Later, in early December, Jim and I flew to Austin for a Texas Sheiks gig at the Saxon Pub, where Stephen Bruton regularly played with his band, the Resentments. The gig was a dream. I do believe we rocked the joint — those Texans were swinging and swaying. I loved it. We also performed live on KUT radio, and it couldn’t have gone better. The interviewer, Jay Trachtenburg, was laid back and well informed about all the players in the room. He was just the guy to guide the proceedings. The whole Austin experience was terrific. I’m really growing comfortable with the place and I’m making new friends every time I get down there.

The Texas Sheiks at the Saxon Pub (photo: Mary Bruton)

After Austin, I flew home for one day, then drove up to The Bay Area where I met up with the Sheiks for a gig at the new Freight & Salvage. The sold-out show was plagued by sound problems, but it didn’t seem to bother the audience. These folks had never heard anything like this band, and when Bonnie Raitt sat in with us… well, that about did it — the cherry was on the sundae. Everyone knows Bonnie has that beautiful, silky voice. But I, for one, keep forgetting what a dangerous guitar player she is. I’ll tell you, she was bendin’ those wires, especially that unwound 3rd string. I can picture an inscription carved into the smooth trunk of an old beech tree: “The Texas Sheiks love Bonnie Raitt.” This in the middle of a big heart. Thanks, Bonnie.

The Texas Sheiks w/ Bonnie Raitt at the Freight & Salvage (photo: Lori Eanes)

Friends came from all over for this performance. This included a surprise visit from none other than Dutch Family member, Peter Steultjens. Wow! He presented Jim and me with framed copies of the photo (used earlier above) showing us climbing a sail on the windmill near Bemmel.

A fellow named Ted Sapphire provided another nice surprise that evening. He brought along an old 1965 Moon-Cusser Coffee House calendar (poster) intending to show to Jim and me. But after he heard the Texas Sheiks, he decided to give it to me outright. How nice is that?

The Moon-Cusser coffee house was active for a few summers in the town of Oak Bluffs on Martha’s Vineyard. The Jug Band played there a few times, and there was no telling who might come to the club. The Simon Sisters – Carly and Lucy – opened for us one summer, and Leonard Bernstein came to hear one of our shows. It’s amazing who played that little place. If you can’t make it out on the blurry photo below, here are highlights of the calendar from June 20th to September 5th 1965: Jim Kweskin and The Jug Band, John Hammond, Dick & Mimi Farina, The Country Gentlemen, Lightnin’ Hopkins, John Hurt, Tom Rush, Doc Watson, The Paul Butterfield Band, The Greenbriar Boys, Jean Redpath, John Koerner and Jackie Washington.

Moon-Cusser Coffee House Calendar, 1965

Whenever we played the Moon-Cusser we tended to linger on the Vineyard and hang out with other musicians. Performers were put up in a big house on the outskirts of Vineyard Haven, off the main road, down a dirt driveway in the middle of a large field. There were no neighbors to bother, so we naturally partied pretty vigorously. It was there that I got to know Butterfield and Bloomfield. I had met them before – Bloomfield in the cellar of Bob Koester’s record store in Chicago in the summer of 1962, and Butterfield at Newport — but it was on the Vineyard that I found out just how jive a couple of Chicago Blues Boys could be. To modify an Ernie Kovacs routine somewhat: “Man, these guys needed someone on radar in case they strayed to close to the truth.” They ran so many head games it got to where if they ever told the truth, no one would believe them. Then you’d hear, “No, really, I swear. Really.” But you never knew.

Another performer I spent time with at the Moon-Cusser House, although not in 1965, was Jose Feliciano. I loved the guy. Haven’t seen him in years, but he could really play, and he had a very sick sense of humor — a good thing. Jose will forever be remembered for taking a silly pop hit called “Light My Fire” and, one year later, transforming it into a hip classic. He’s one of those guys who — although recognized as a significant talent — is even better than you think.

Then there was John Hurt — one of the sweetest guys I ever met. He had that wide, easy smile, funny hat, and he looked just like Jiminy Cricket. We took him to the beach one day, and when he saw a couple of surfers offshore riding their boards, he pointed out to where they were and said, “Look at those wave saddles!”

Fritz Richmond and I used to collect planks of wood off the Island’s beaches. In those days, in order for cargo ships to unload quickly when they reached port, they would start to uncrate their goods before rounding Cape Cod for Boston, or perhaps as they cruised south towards the New York area terminals. The lumber used for those crates was thrown overboard in the process and much of it would end up washed ashore on the south side of Martha’s Vineyard. Philippine Mahogany of various grades, oak and the occasional piece of birch or maple might be found there. We would collect the wood with a four-wheel drive truck, lay the wood out to dry and then drive it up to Fritz’s parents’ house in Newton. There, in his father’s woodworking shop, we would plane, sand, drill and turn the wood to fashion shelves, beds, washboard frames, chair rung replacements, interiors of VW buses, whatever. This was mostly Fritz’s passion but, I loved helping him.

One time we laid out what must have been five or six hundred board feet of salvaged wood on the field in front of the Moon-Cusser House. John Hurt was being driven to the house one day and he saw the wood. Curious, he walked over to us while we were adjusting and flipping the planks for proper airing. He took his thumbnail and scratched one of the boards. “This is cypress,” he said. Then he scratched another. “This is cypress too.” Then another and another — “My goodness, this is cypress too.” He scratched a few more boards and said the same thing over and over again in that sweet, whispery voice of his. John obviously loved cypress, and we weren’t going to say anything to bring him down.

So, as you can see, that calendar given to me by Ted Sapphire last December at The Freight & Salvage means a lot to me. It’s brought back a lot of fond memories. I’ve hung it on the wall next to my desk in an acid-free, archival frame for safe keeping.

Jim and I said goodbye to the Sheiks and flew out the next day to Portland, OR. There we played a venue called Mississippi Studios with members of Fritz Richmond’s old jug band, The Barbeque Orchestra. These guys swing hard. I was sorry their guitarist “Turtle” Vandemarr wasn’t able to join us, but “Spud” Siegal, “Doc” Stein and “Stew” Dodge played great. I was so tired and having so much fun I forgot to make a mistake. I think Jim had the same problem.

Finally, it was time to get home and prepare for Christmas. That was it for 2009.

This year will find me in Canada, Texas, Japan, the Mid-West, New England, and who knows where else. There are a couple of album projects bubbling under and we’ll see which one comes to the surface.

Take care and best wishes,

Geoff